The Republican Party is having none of your pantywaist "family values" rhetoric. Frankly, that whole "self-control" business, the old fatherly advice to "keep it in your pants" -- that stuff is just repression. Haven't the Dems ever even heard of Sigmund Freud?

If it were not already clear, this morning's news offered proof positive that the GOP stands for a proud, masculine ethic of uninhibited and unembarrassed sexuality. For men. Women are still encouraged to smile demurely and pretend they don't know the naughty words.

You see, Newt Gingrich went on TV to defend the Republican nominee, and when Megyn Kelly asked him about the many recent claims of sexual harassment against Donald Trump, Gingrich accused her of being -- wait for it -- "fascinated with sex."

Savor the moment. Here is Gingrich, a serial adulterer, defending Trump, another serial adulterer, and accusing a reporter of being sexually compulsive. Both men have repeatedly disregarded their vows and destroyed their marriages in pursuit of the next erotic thrill. So has Trump's other most vocal surrogate these days, Rudolph "Divorced His Second Wife on TV" Giuliani. All three present themselves as burly men's men, the kind who stand around in locker rooms bragging about how much women love their attention before they hit the courts (or links, or whatever). Never mind that in reality they are fat balding senior citizens with prostate problems whose unreconstructed understanding of masculinity makes Don Draper look positively enlightened.

But Kelly is the one fascinated by sex. because she does her job, and pursues relevant questions about the temperament, behavior and truthfulness of a presidential candidate.

Double-standard, anyone?

Wednesday, October 26, 2016

Tuesday, October 25, 2016

A Pretty Good Collect

We complained recently about the translation of a certain medieval collect as it appears in Evangelical Lutheran Worship. In fairness, however, it must also be said that in some cases ELW's translations are pretty good. One of the better ones is coming up soon.

The first of two collects offered for Reformation Day (ELW #215) comes to us from the 1539 Saxon church order, where it is prescribed for Wednesday at Vespers. (And how wonderful must it have been to serve a church that needed collects for each day's Office!) It reads:

The prayer is not found in the 1917 Common Service Book, but does appear in both The Lutheran Hymnal (1941) and the Service Book and Hymnal (1962), in this form:

In addition, the reference to God's Name disappears, and does not return in the successor versions. Why? We cannot even hazard a guess; prayers that God will act "for thy name's sake" are not uncommon, and have plenty of Biblical precedent.

The collect was modernized for the Lutheran Book of Worship (1978) thus:

ELW takes a few more liberties with the underlying text:

The first of two collects offered for Reformation Day (ELW #215) comes to us from the 1539 Saxon church order, where it is prescribed for Wednesday at Vespers. (And how wonderful must it have been to serve a church that needed collects for each day's Office!) It reads:

Herr gott himlischer vater: wir bitten dich, du woltest deinen heiligen geist in unsere herzen geben, uns in deiner gnade ewig zu erhalten, und in aller anfechtung zu behüten, wöllest auch allen feinden worts umb [sic] deines namens ehre willen wehren und deine arme christenheit allenthalben gnedig [sic] befrieden, durch Jesum Christum deinen lieben son unsern herrn.A very literal English translation, courtesy of Father Fritz von der Brick-Gothic, is:

Lord God, Heavenly Father, we ask that You would put Your Holy Spirit into our hearts, so that we will remain in Your [grace and] mercy and be safe in all temptation. [We also ask] that for the sake of Your [Holy] Name You would strengthen us against the words of our enemies, and graciously give peace to Your beleaguered Christians everywhere, through Jesus Christ, Your beloved Son, our Lord.

O Lord God, heavenly Father, pour out, we beseech thee, thy Holy Spirit upon thy faithful people, keep them steadfast in thy grace and truth, protect and comfort them in all temptation, defend them against all enemies of thy Word, and bestow upon Christ’s Church militant thy saving peace; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who liveth …A few key changes appear to have taken place at this stage. Chiefly, the language for those calling upon God has been rendered less idiosyncratic. The intimacy of "our hearts" has been replaced by a more generic appeal on behalf of God's "faithful people," and the somewhat plaintive call to help "your poor Christendom" by a more generic reference to "Christ's Church Militant." One might call this a "de-pietizing" of the base text, if that were a word.

In addition, the reference to God's Name disappears, and does not return in the successor versions. Why? We cannot even hazard a guess; prayers that God will act "for thy name's sake" are not uncommon, and have plenty of Biblical precedent.

The collect was modernized for the Lutheran Book of Worship (1978) thus:

Almighty God, gracious Lord, pour out your Holy Spirit upon your faithful people. Keep them steadfast in your Word, protect and comfort them in all temptations, defend them against all their enemies, and bestow on the Church your saving peace; through your Son, Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever.Clause by clause, this is the TLH version shorn of its Jacobean trappings, with only two exceptions. We ask God to keep us steadfast not in "grace and truth" but in his "Word," no doubt in order to remind us of Luther's famous hymn. This is effective rhetorically, but does have the sad effect of removing from the prayer the word "grace," which is essential to Luther's theology. And "Christ's Church Militant" is now simply "the Church" -- a reasonable rendering, but sadly without the claim that this church belongs to God.

ELW takes a few more liberties with the underlying text:

Almighty God, gracious Lord, we thank you that your Holy Spirit renews the church in every age. Pour out your Holy Spirit on your faithful people. Keep them steadfast in your word, protect and comfort them in times of trial, defend them against all enemies of the gospel, and bestow on the church your saving peace, through Jesus Christ, our Savior and Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever.

It's not a bad rendering. "Enemies of the gospel" is an improvement over LBW's mere "enemies," which left open the possibility that we wanted God to help us in our sporting events or international affairs. We still don't know whose church it is, but perhaps we are expected to infer from context.

One clause sticks out. We do not now merely call for the Spirit to be given us, we are first reminded that this Spirit continually renews the church. Why is that idea added?

The most obvious reason is to direct our thoughts to the Reformation itself. If so, this is a better choice than adding, for example, "You gave us Luther, Melanchthon and Chemnitz to purify the doctrine of your hitherto corrupted church," or something just as Missourian.

Another, less appealing, possibility is that the ELW editors are captive to the proposition that collects have a definite form, and must by nature begin with a recollection of God's mighty deeds. This proposition is widely promoted by liturgical handbooks, but is a matter of observation rather than prescription. A quick glance at the medieval sacramentaries reveals that a great many collects do not in fact so begin.

In either case, the added clause demonstrates a singular characteristic of ELW, namely its steadfast refusal to settle for fewer words and images when more will suffice. In every case we have bothered to examine, the ELW prayers add to their base texts, rather than taking away from them. (Even Reed's fine Eucharistic Prayer has a mysterium fidei added, Romanizing a text inspired by the East.) One wonders sometimes whether the editors were closet Mozarabs, so little do they seem interested in Edmund Bishop's "sobreness and sense."

Still. All told, ELW Prayer 215 is neither more nor less apt a rendering of its 1539 original than the parallels in other modern service books. What they all lack, in our opinion, is the personal and emotive touch of the Reformation original -- our hearts, our beleaguered (or "poor") condition, our sense of belonging to God.

Thursday, October 13, 2016

Eliminate the Undergraduate Degree

A common question with regard to preparation for ordained ministry is "How much can we live without?" Several emergent circumstances prompt this question -- decline in seminary enrollment, the difficulty of church bodies to subsidize their seminaries, the crushing burden of academic debt on people who have been painstakingly prepared for a profession in which full-time work is becoming scarce. Naturally, churches ask how to control the cost of preparing their ministers, a question which leads just as naturally to the follow-on: which aspects of the present preparatory routine are dispensable?

For those who do not know, the preparation of a Protestant minister, in the United States, typically looks like this:

It amounts to nine or ten years of study, the last few of them 12-month years during which postulants have no vacation time in which to earn any money. They are all but guaranteed to graduate penniless, hungry and in debt.

In fairness, churches have not mindlessly insisted upon adherence to this general program. For years, they have experimented with variations. Especially popular these days are "terminal internships," in which a candidate completes the entire classroom course of study, and is then placed in a parish as "vicar," under the periodic (but not daily) supervision of a neighboring pastor. The expectation is that after ordination the vicar will became pastor to the same parish. Other less popular variations include distance learning, which allows the student to continue working and avoid the costs of residential study, and programs that simply waive some academic requirements for older postulants from "emerging ministries," meaning especially minority communities.

None of these is bad, but none of them is a magic bullet, either. Terminal internships may place new pastors in difficult situations without adequate mentoring, and in any case save them only the costs of the internship year. TEEM and similar programs save a lot more money, but create the very serious risk of burdening congregations with pastors who are not intellectually adequate to the task, or whose adequacy is limited to the very specific location to which they were ordained, and do not transfer well to other parishes.

Over and over, it comes back to "What can we cut?" Is a decent grounding in Biblical languages more or less important than a summer of hospital chaplaincy or a year of daily supervision? Is a grasp of Reformation history more or less important than an a third semester of homiletics? All of these things matter; all of them are important to the effective conduct of pastoral work.

But do you know what is not important? A degree in biology. Or aeronautics, or even "religion" as that discipline is understood by the modern academy. These are undergraduate studies, of great interest by themselves and in some cases of direct value to potential employers. They are not, however, subjects absolutely required for pastors and theologians.

So let's make studies in divinity an undergraduate subject.

By which I mean: let us agree upon a course of study which can, in four years, prepare a capable high school graduate to carry out the duties of a parish pastor. Teach them, in the course of four years, the things we now teach them in three, and add to that a smattering of "elective" subjects -- music and art would be the most professionally useful, but such matters could be negotiated. So might an optional fifth year of study, in which an advanced degree (rather like the Th.M. or S.T.M.) could be granted.

Such a plan might give new life and purpose to our moribund seminaries. The course of study could not be as diffuse as those which lead to the typical BA and BS degrees -- and this degree would be neither of those. It would have to focus more narrowly on theological subjects, which most colleges are unprepared to teach, but at which seminaries excel. Therefore, a seminary is the natural institution to offer such a degree, perhaps after enlarging its faculty a bit or in conjunction with a larger school.

But the chief virtue of such a plan is that it could potentially save a fortune for those with an early vocation. Of all the costs incurred in the "typical"process, the undergraduate education is surely the greatest for most people, and yet paradoxically it is the one with the least obvious practical value.

Oh, downsides are obvious. Pastors prepared this way would be less mature in years, and likely emotions, than those to which parishes are accustomed. Moreover, they might lack exposure to fields of study -- especially sciences both natural and social -- with genuine, if secondary value for a theologian. Second-career pastors gain nothing from this plan, although they do not lose anything either. There are no doubt other difficulties as well. But still: It. Saves. A. Fortune.

What do you think, readers?

For those who do not know, the preparation of a Protestant minister, in the United States, typically looks like this:

- a four-year undergraduate degree in any subject, although the humanities are preferred;

- a three-year graduate program in "divinity," which quaint word indicates a combination of Biblical, historical and theological studies;

- practical work, normally taking the form of field work while in seminary, Clinical Pastoral Education and (for all Lutherans, at least) a year or so of (very lightly paid) parish internship.

- Lutheran students who have graduated at a non-Lutheran school may also be required to complete a year of residential study at one of their own denomination's seminaries.

It amounts to nine or ten years of study, the last few of them 12-month years during which postulants have no vacation time in which to earn any money. They are all but guaranteed to graduate penniless, hungry and in debt.

In fairness, churches have not mindlessly insisted upon adherence to this general program. For years, they have experimented with variations. Especially popular these days are "terminal internships," in which a candidate completes the entire classroom course of study, and is then placed in a parish as "vicar," under the periodic (but not daily) supervision of a neighboring pastor. The expectation is that after ordination the vicar will became pastor to the same parish. Other less popular variations include distance learning, which allows the student to continue working and avoid the costs of residential study, and programs that simply waive some academic requirements for older postulants from "emerging ministries," meaning especially minority communities.

None of these is bad, but none of them is a magic bullet, either. Terminal internships may place new pastors in difficult situations without adequate mentoring, and in any case save them only the costs of the internship year. TEEM and similar programs save a lot more money, but create the very serious risk of burdening congregations with pastors who are not intellectually adequate to the task, or whose adequacy is limited to the very specific location to which they were ordained, and do not transfer well to other parishes.

Over and over, it comes back to "What can we cut?" Is a decent grounding in Biblical languages more or less important than a summer of hospital chaplaincy or a year of daily supervision? Is a grasp of Reformation history more or less important than an a third semester of homiletics? All of these things matter; all of them are important to the effective conduct of pastoral work.

But do you know what is not important? A degree in biology. Or aeronautics, or even "religion" as that discipline is understood by the modern academy. These are undergraduate studies, of great interest by themselves and in some cases of direct value to potential employers. They are not, however, subjects absolutely required for pastors and theologians.

So let's make studies in divinity an undergraduate subject.

By which I mean: let us agree upon a course of study which can, in four years, prepare a capable high school graduate to carry out the duties of a parish pastor. Teach them, in the course of four years, the things we now teach them in three, and add to that a smattering of "elective" subjects -- music and art would be the most professionally useful, but such matters could be negotiated. So might an optional fifth year of study, in which an advanced degree (rather like the Th.M. or S.T.M.) could be granted.

Such a plan might give new life and purpose to our moribund seminaries. The course of study could not be as diffuse as those which lead to the typical BA and BS degrees -- and this degree would be neither of those. It would have to focus more narrowly on theological subjects, which most colleges are unprepared to teach, but at which seminaries excel. Therefore, a seminary is the natural institution to offer such a degree, perhaps after enlarging its faculty a bit or in conjunction with a larger school.

But the chief virtue of such a plan is that it could potentially save a fortune for those with an early vocation. Of all the costs incurred in the "typical"process, the undergraduate education is surely the greatest for most people, and yet paradoxically it is the one with the least obvious practical value.

Oh, downsides are obvious. Pastors prepared this way would be less mature in years, and likely emotions, than those to which parishes are accustomed. Moreover, they might lack exposure to fields of study -- especially sciences both natural and social -- with genuine, if secondary value for a theologian. Second-career pastors gain nothing from this plan, although they do not lose anything either. There are no doubt other difficulties as well. But still: It. Saves. A. Fortune.

What do you think, readers?

Friday, October 07, 2016

"Wrangling Over Words"

Saint Paul -- or, if not Paul, then whoever actually wrote the Second Letter to Timothy -- uses a curious expression, and one which may excite the imagination of a few preachers. He advises young Timothy on how to encourage God's People to endure as Paul himself has endured for the sake of the Gospel. First, he quotes a now-lost hymn (paralleled in Polycarp's Letter to the Philippians) about dying with Christ in order to live with Christ; then he says:

This is good advice, especially in an Hellenistic context. Greeks were notorious in the ancient for their love of philosophical argument. They would talk a subject to death, it was commonly said, rather than kill it like men. Even Greeks themselves grew impatient with the endless hairsplitting that seemed to cast doubt upon the received wisdom of religion, family and nation. Hence Socrates' unfortunate final cocktail.

Theologians, who are first cousins to philosophers, have also been known to talk a subject to death, and extract from a close reading conclusions opposed to the "common sense" of the average hearer. For the most part, this is a good thing; the average hearer does not know what he is listening to. It is astonishing to us how many Christians manage to leave Sunday service, having spent an hour hearing the Prince of Peace blessing the peacemakers, convinced that Jesus wants them to kill Mooslims or build a wall against immigrants. The task of theology is to challenge sloppy religious thinking, and the first tool in its box is attention to the actual language of Scripture. Words matter.

But as any indulged child will admit after too long in an ice-cream parlor, one can have too much of a good thing. Many Christians, including some of the educated and articulate, tire of speculation that does not lead to action. Too much talk, or worse yet the wrong kind of talk, will douse the coals once lit by the Spirit. We have all seen it; indeed we see too much of it, as passionate believers begin to doubt that their belief has either a firm basis or a logical conclusion, and so slip away into the rolls of the "inactive."

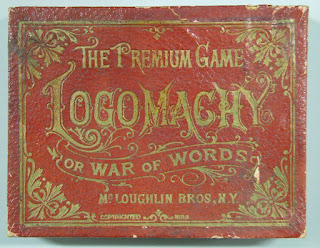

Anyway, back to Paul. What we render as "wrangling over words" is in fact a single word, logomacevw. It has an English cognate, logomachy, an argument over words. Its use in English is rare and generally jocular. The Victorians played a board game by this name; Roger Angell once asked how best to measure the effectiveness of a baseball pitcher, and concluded that "here, as in other parlous areas of the pastime, the answer must be left to the writers and the fans, and to the thousand late-night logomachies."

Do not be fooled by the appearance of playfulness. Greeks used -macevw combinations strategically, to tell a story about their deepest values. It was not always a very pleasant story, either. Two common tropes in Greek art are the "centauromachy" and the "Amazonomachy." Each shows the pitched battle and ultimate triumph of Greeks over their monstrous opposites -- beastly men and warlike women.

While we moderns may romanticize both centaurs (think of noble Firenze in the Harry Potter books) and Amazons (Wonder Woman, or any of a zillion other warmings-over of the Bachofen thesis), the Greeks were having none of it. Such things were monsters, the funhouse-mirror reflections of their own values: reason and masculinity. Their conquest, if only in art, was a victory for the self-image of Greek men.

So what does it mean when Paul, or perhaps his slightly more Hellenized follower Pseudo-Paul, applies this rhetorical strategy to words, rather than horses or women? Perhaps the idea is to encourage Christians in a life of what is today called praxis: faith active in love, rather than in disputation and speculation. And the point is sharpened by all those Parthenon friezes; as pagans labored to defeat the temptations of brutishness and femininity, so we Christians must defeat the temptation to argue amongst ourselves over the fine print of our confession.

[W]arn them before God that they are to avoid wrangling over words, which does no good but only ruins those who are listening. (2:14b, NRSV)"Wrangling," which makes Americans think of horses, may not be the best translation. Nor is the KJV's "strive," with its undertones of ambitious effort. We would prefer a more mundane "warn them against bickering over words."

This is good advice, especially in an Hellenistic context. Greeks were notorious in the ancient for their love of philosophical argument. They would talk a subject to death, it was commonly said, rather than kill it like men. Even Greeks themselves grew impatient with the endless hairsplitting that seemed to cast doubt upon the received wisdom of religion, family and nation. Hence Socrates' unfortunate final cocktail.

Theologians, who are first cousins to philosophers, have also been known to talk a subject to death, and extract from a close reading conclusions opposed to the "common sense" of the average hearer. For the most part, this is a good thing; the average hearer does not know what he is listening to. It is astonishing to us how many Christians manage to leave Sunday service, having spent an hour hearing the Prince of Peace blessing the peacemakers, convinced that Jesus wants them to kill Mooslims or build a wall against immigrants. The task of theology is to challenge sloppy religious thinking, and the first tool in its box is attention to the actual language of Scripture. Words matter.

But as any indulged child will admit after too long in an ice-cream parlor, one can have too much of a good thing. Many Christians, including some of the educated and articulate, tire of speculation that does not lead to action. Too much talk, or worse yet the wrong kind of talk, will douse the coals once lit by the Spirit. We have all seen it; indeed we see too much of it, as passionate believers begin to doubt that their belief has either a firm basis or a logical conclusion, and so slip away into the rolls of the "inactive."

|

| A Greek warrior kills a centaur |

Do not be fooled by the appearance of playfulness. Greeks used -macevw combinations strategically, to tell a story about their deepest values. It was not always a very pleasant story, either. Two common tropes in Greek art are the "centauromachy" and the "Amazonomachy." Each shows the pitched battle and ultimate triumph of Greeks over their monstrous opposites -- beastly men and warlike women.

While we moderns may romanticize both centaurs (think of noble Firenze in the Harry Potter books) and Amazons (Wonder Woman, or any of a zillion other warmings-over of the Bachofen thesis), the Greeks were having none of it. Such things were monsters, the funhouse-mirror reflections of their own values: reason and masculinity. Their conquest, if only in art, was a victory for the self-image of Greek men.

|

| Amazonomachy, from a Roman sarcophagus |

So what does it mean when Paul, or perhaps his slightly more Hellenized follower Pseudo-Paul, applies this rhetorical strategy to words, rather than horses or women? Perhaps the idea is to encourage Christians in a life of what is today called praxis: faith active in love, rather than in disputation and speculation. And the point is sharpened by all those Parthenon friezes; as pagans labored to defeat the temptations of brutishness and femininity, so we Christians must defeat the temptation to argue amongst ourselves over the fine print of our confession.

Thursday, October 06, 2016

The Prayer of the Day: A Case Study

The collect for this coming Sunday provides an interesting look at how traditional prayers are rendered for modern worship books. We are looking, specifically, at the prayer for Lectionary 28 C (formerly known as Proper 22 C) found in Evangelical Lutheran Worship and related publications of Augsburg-Fortress Press.

Here is the Latin original, from the Gelasian Sacramentary:

Here is the traditional Book of Common Prayer version, which was used among Anglophone Lutherans at least through the life of the Service Book and Hymnal (for the 19th Sunday after Trinity):

The Lutheran Book of Worship does not seem to have used this collect (or if so, we cannot find it), but ELW's ambitious three-years cycle of Prayers of the Day requires all praying hands on deck. Here is the current version:

On the other hand, its editors have often made questionable decisions in their handling of the old material, feeling especially free to substitute their own theological and cultural concerns for those of the ancient and medieval communities that created them. That's not a crime; the Reformers did a lot of the same thing. But the Reformers were working with texts that they considered grossly corrupt on account of neo-Pelagianism, and so removed petitions to the saints and so forth. These modern changes seem both smaller and more arbitrary. In some cases, although not this one, they result in prayers whose terse Latin character has been diluted by the intrusion of foreign ideas, making the whole thing longer and less pithy.

We don't hate ELW. Really we don't. (Except for the Psalter, which we do hate with a Psalm 139-worthy perfect hatred). ELW is a physically beautiful book, the result of more hours of work than we can ever imagine. But from the Mass settings that simply stop halfway through to the arbitrary re-translations of classic prayers, it is a frustrating book for us to use. We hope for better next time.

Here is the Latin original, from the Gelasian Sacramentary:

Omnipotens et misericors Deus, universa nobis adversantia propitiatus exclude: ut mente et corpora pariter expediti, quae tua sunt, liberis mentibus exsequamur. [Alford, Liber Sacramentorum etc. (1894), p. 232.]Like many of the medieval collects, it is a bit tricky. Father John Zulhsdorf, a far more accomplished Latinist than we at the Egg, offers this "slavishly literal" translation:

Almighty and merciful God, having been appeased, keep away all things opposing us, so that, having been unencumbered in mind and body equally, we may with free minds accomplish the things which You command.We would render quae tua sunt more literally still as "your things," as in the ELCA's popular slogan, "your things, our hands." But close enough.

Here is the traditional Book of Common Prayer version, which was used among Anglophone Lutherans at least through the life of the Service Book and Hymnal (for the 19th Sunday after Trinity):

O almighty and most merciful God, of thy bountiful goodness keep us, we beseech thee, from all things that may hurt us; that we, being ready both in body and soul, may cheerfully accomplish those things which thou commandest; through Jesus Christ our Lord. AmenNotice a few key translation choices. Propitiatus, the root meaning of which is in the favorable disposition that comes from having been soothed or, as we say in English, propitiated, is rendered "of thy bountiful goodness." It marks a change in grammar, and perhaps a dilution of the original idea, but it results in good English. "Cheerfully," on the other hand, sounds almost trite, especially against the inspiring idea of doing God's work "with free minds."

The Lutheran Book of Worship does not seem to have used this collect (or if so, we cannot find it), but ELW's ambitious three-years cycle of Prayers of the Day requires all praying hands on deck. Here is the current version:

Almighty and most merciful God, your bountiful goodness fills all creation. Keep us safe from all that may hurt us, that, whole and well in body and spirit, we may with grateful hearts accomplish all that you would have us do, through Jesus Christ, our Savior and Lord. Amen.It's not bad, as ELW collects go. God is addressed in conventional language, and no manatees are mentioned. We will certainly pray it without hesitation. But please do notice a few points of difference from its models.

- Far from having been appeased, God's favorable disposition, or "goodness," is now said to "fill all creation." Apparently universa has been read in relation to propitiatus rather than nobis adversantia. Our command of the grammar isn't good enough to criticize, but ... we are suspicious.

- Christians are said to be "whole and well," rather than "prepared," i.e. for work. The delightful image of the baptized marching expediti, like lightly-burdened soldiers, has been set aside. Wholeness and wellness are certainly Biblical ideas, and fit nicely with this week's lessons about leprosy cures. But they are also, it must be said, modern preoccupations. It is not fair to look at this substitution and cry out "therapeutic religiosity!" -- but neither does that make the choice a good one.

- Our "free minds" -- or hearts, or even souls; we won't fight you on that -- have been changed yet again. We are no longer merely "cheerful," but now "grateful." Again, the concept of gratitude meshes nicely with the recent direction of the lectionary (although the Samaritan leper, technically, does not give God thanks so much as praise). But again also we see a modern preoccupation replace an ancient one. Gratitude is much spoken about in modern churches, especially with reference to stewardship; we are to do good works because God has done a good work for us. But changing the focus this way, we lose the subtler point that in Christ we have been set free not only from sin but from obligation; we can now pursue goodness for its own sake, following its path back toward the Source of all that is good.

On the other hand, its editors have often made questionable decisions in their handling of the old material, feeling especially free to substitute their own theological and cultural concerns for those of the ancient and medieval communities that created them. That's not a crime; the Reformers did a lot of the same thing. But the Reformers were working with texts that they considered grossly corrupt on account of neo-Pelagianism, and so removed petitions to the saints and so forth. These modern changes seem both smaller and more arbitrary. In some cases, although not this one, they result in prayers whose terse Latin character has been diluted by the intrusion of foreign ideas, making the whole thing longer and less pithy.

We don't hate ELW. Really we don't. (Except for the Psalter, which we do hate with a Psalm 139-worthy perfect hatred). ELW is a physically beautiful book, the result of more hours of work than we can ever imagine. But from the Mass settings that simply stop halfway through to the arbitrary re-translations of classic prayers, it is a frustrating book for us to use. We hope for better next time.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)